the sound of the internet, oubliettes, tfw collective nostalgia, mfer you can live at the mall!

What does the internet sound like? (Part 1 - Revisiting the past)

When I posed this question on Twitter, I realized that perhaps I should have specified representative of the internet today, and not so much cumulative personal attachments from the past. But I’m grateful for my lack of articulate precision (for once) because the responses provided an enlightening survey of particular sonic associations reflective of our individual and collective growth alongside the internet, both as a construct and as a virtual space. What is the internet if not a place for personal use, and an extension of ourselves and the memories we form on, and through, it over the years?

A couple people mentioned the Postal Service, two others mentioned Oneohtrix Point Never and Dan Lopatin’s work under other monikers. Mashup music like Girl Talk, Radiohead’s Kid A, witch house, the Hackers soundtrack. Some of these might bring to mind specific spheres of the internet you’ve traversed at different moments in your life, at the height or tail-end of cultural zeitgeists and their respective trends. It was cool to see everyone’s associations and consequently confront my own specific internet memories tied to some of the responses. Take the Postal Service, for example. I would not necessarily think of this group in relation to the internet, especially not the current incarnation of the internet, but it did remind me of going on Xanga as a tween and lurking schoolmates’ blogs, hearing “Such Great Heights” embedded into their custom layouts and set to auto-play. Never Angeline North offered Black Dresses as the sound of trans twitter, which emphasizes that platform and era must be taken into consideration along with milieu and socio-cultural experiences and interests—it’s a nexus of overlapping and interrelated things. Medium insofar as blog, application, game, chatroom, and so on, correlates with message, which would be the particular sound that happens to become a defining referent.

However, that wasn’t enough for my research purposes, so I googled “what does the internet sound like.” That yielded a few articles regarding a documentary series on cloud computing, and which describe how the data centers whose massive servers hosting our digital archives produce a multilayered buzzing and humming din. Dissatisfied with that literal result, I rephrased my search to “music that sounds like the internet,” and was presented with, unsurprisingly, similar artist suggestions for the band called the Internet. But one of the top results was a link to a piece in Rolling Stone from last year and this firmly placed me back on the track I had initially set out on. The article presents the phenomenon of “the most mysterious song on the internet,” which made me feel disconnected from the web because this was (supposedly) old internet lore I had managed to miss.

After giving it a listen, I was surprised by how unremarkable it is. That isn’t to say it’s bad, though, just not captivating enough to pursue for so long; in fact, it sounds similar to some of the Soviet new wave I shared last week. It sounds like a gloomy synth-pop anthem you might hear muffled from outside while passing any dive bar in California. (Honestly, it’s been a relief not going to bars and hearing the same DJs play the same songs every set!) And that’s the point. That it sounds familiar but unplaceable. It aligns with the doomer shit it seems like everyone who hopped on the goth-and-darkwave revival train listens to ad nauseam.

Although the mystery surrounding the song does sort of produce a creeping sense of paranoia in me, as if it has the ability to curse those who listen to it. If I think about it for too long, I start convincing myself it’s a psyop, some sort of experiment in implanting artificial cultural memories to test how receptive the masses are in re-claiming simulated ghosts from the past. That’s a road I won’t go down, though.

The quest to identify the song is “[…] the story of people longing for community in the digital era. But it’s also become something bigger,” writes David Browne in the Rolling Stone piece. “Even if the case is never solved, it has briefly returned the pre-Google mystique to music [...].” Sure. I’ll give it that. People love the feeling of discovery, and maybe even more when they get to share the rush that comes with it with others. The process of discovering this song pursuit brings us back to my initial question: what sound is representative of today’s internet? The fact of the matter is that I was anticipating confirmation bias after watching two documentaries in quarantine that center on and, in some respect, attempt to dissect the inhabitants of particular online communities who possess similar values and operate with similar behavior online.

Feels Good Man & TFW No GF

I watched TFW No GF when it was free during SXSW’s showcase on

A̓̑ͩm̃̅ͨ̈aż͑ôn̄ͮ͊̽͗ ͤͫͭͯ͋̚Pͧ̂ͥ̇̎ͦͬr͋̾̓́ì̈͐͗̇͒̍m̾͑̏ͬȇ̐̚ early on in quarantine and rented Feels Good Man last month.

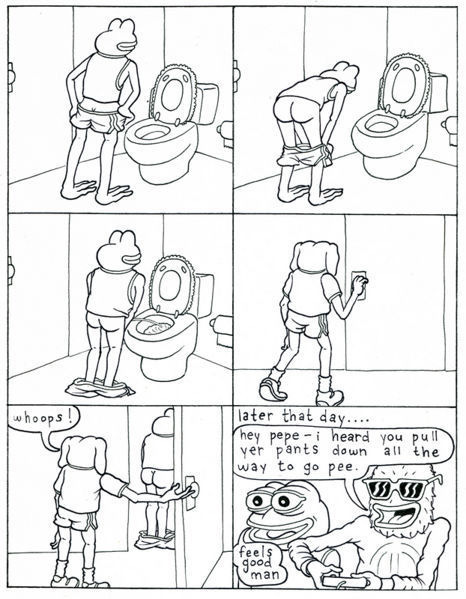

It feels necessary to call attention to the obvious, that some construction of “feeling” is present in the films’ titles, both referring to sensory and emotional experience, which I think is instrumental in understanding how these images take on a life of their own when used as currency to relate to others. “That feel when,” or “that feeling when,” (TFW) is an internet acronym and meme format that exists as a prefix to any emotionally charged relatable experience, either positive or negative, and the origins of “feels good man” lie in, well…see below. Perhaps could use further research from a phenomenologist or affect theorist.

from Matt Furie’s Boy’s Club

Kantbot, one of the five subjects of TFW No GF, claims that Wojak, the tfw meme template mascot, and Pepe, the decontextualized frog character-cum-meme-cum-hate symbol, represent the duality of online personae. According to his reasoning, Pepe is the “troll self” and public persona, and Wojak is representative of inner turmoil, insecurity, and feelings of inadequacy. Essentially, a new iteration of the Comedy and Tragedy masks. Both films depict the damaging effects of going whole hog in being an edgelord online and becoming irony poisoned beyond recognition on personal and social levels, all of which has been written about at length across the internet. What I am most interested in between the two documentaries are their soundtracks in relation to their online subculture subjects. I was immediately struck by some similarities they shared.

“The city is haunted / And nobody loves me”

The opening animated sequence of Feels Good Man features “Living in Hell,” a song by Cobra Man, a group I was unfamiliar with when I identified it with Shazam. It has the same hypnagogic power pop sound that music by Ariel Pink and John Maus possess, but probably came with a lighter licensing fee. Of course, the Shazam app suggested John Maus as a similar artist after identifying the song. TFW No GF’s soundtrack features music from John Maus and Ariel Pink.

It is by sheer coincidence that I have mentioned Ariel Pink twice in this newsletter so far. Don’t get it twisted like I’m this huge super fan of his. But if I had to make a distinction between Maus and Pink, I would say Pink’s music is more woozy, psychedelic-heavy, and in the lineage of white male lo-fi freakers like Gary Wilson, Martin Newell (of Cleaners from Venus), and R. Stevie Moore. There is something to be said about his 60s freak-out inspired music, and that style’s resounding aural and aesthetic reverberations felt in the early San Francisco tech boom in the 90s built upon 60s philosophies, but maybe that’s a development for another post. I’m not really interested in writing about Ariel Pink as much as I am interested in John Maus. Please don’t think about Ariel Pink while you read this. Although their musical output walk hand in hand like cousins, my main focus is the attitude that John Maus’s music seems to connect with and provide texture to the online communities of 4chan and, maybe to a lesser extent, reddit. I’m painting with broad strokes here, I’m not trying to be prescriptive, just casting this thought out there as if it were a popcorn kernel lodged between my back teeth; I just need to get it out, even if it’s a little messy!

John Maus is almost like a Scott Walker figure. He takes pop conventions to a darker, bleaker place, like a hungry bear dragging a doe into a cave, and with a similar sense of irony, even with his crude and stripped lyrical offerings. His use of baroque chordal harmonies and the low frequencies he records under give his music the effect of hearing a spectral transmission from the past. But his music is hostile and charged with a frustrated and libidinal energy that is undeniably very current. With its abrasive edge smoothed over by woolly echoes and layered rhythms, it’s a sound that evokes a certain NuMasc sensitivity, nihilistic bent, detachment, and alienation that it seems like these two films find synonymous with the attitudes of misfits and trolls, or at least the notion of online and offline mischief and mayhem, and the spaces they inhabit on the web.

Barring the Cobra Man song, Feels Good Man’s score by Ari Balouzian and Ryan Hope is more in the minimal tradition of Philip Glass, the early synth compositions of Tomita, and the moody, hauntological offerings of The Caretaker, the latter which, along with John Maus, serve as perceptible precursors to vaporwave. The score is baleful, meditative, and more cinematic, but its wistful atmosphere present in tracks like “MATADOR” capture the spirit of the lost futures Matt Furie could have had with Pepe while also characterizing the foreboding and anxiety-inducing qualities of the internet. The vibrating strings and gauzy, sweeping circular synth chords of “HOPE” build up to a swell and foreground the documentary’s cathartic release, emphasizing the past’s refusal to quit haunting the present while also intimating we’ve reached a sort of place of no return, at least based off our fractured media landscape.

In a piece for Resident Advisor, Adam Harper writes,

But not all online music is "about" or "because of" the internet or the wider digital world, and the term "online underground" I use doesn't imply any one style or aesthetic, only a mode of distribution.

Occasionally, however, you see the term "internet music" or "net music," which tends to imply music that is somehow internet-like, conflating it with music that's online, much like the phrase "net art" can imply the internet as a subject matter just as much as a medium. The difference can be seen in the comparison of a website like Rhizome's tumblr (internet or post-internet art) with deviantART (which is just art that happens to be on the internet). To confuse "internet music" with music that is merely online is to confuse, as so many people do, indie music—a rugged, maybe naive rock or pop sound—with independent music—music that is produced away from the major music industry. No kind of music, and certainly no particular kind of "bad music" (poor quality music, naive music, excessive music) flows as a natural consequence of a certain mode of distribution, whether independent or online.

I don’t consider John Maus “internet music.” I also don’t think it’s solely the nostalgia factor of the hyper-compressed video game-adjacent sound that gels with channers and redditors either.

Furthermore, I think of vaporwave and hyperpop PC Music acts as titrations of the internet, in addition to their adoption of consumerism and corporate branding aesthetics, as a modality being absorbed and injected into music, especially since the latter are the result of having traveled through different pipelines to arrive at their current trajectories. That royalty-free kinderbeat baby music (I don’t know what to call it) you hear in youtube haul and unboxing videos is probably a wider encompassing example of “internet music,” but I digress.

Somehow all these disparate micro-genres and classifications go back to a single thought in the context of history. So truth be told, I don’t know what the next big thing is. But I don’t know—it’s all speculation, isn’t it?

—John Maus, SPIN interview (2017)

I am out of my element here as I am not an authority on music theory, but this primer on fugues helped me realize that perhaps John Maus’s music tracks with dark recesses of the web because his compositions have tapped into something that feels inherently old and tenebrous, but also close to computer logic. Consider the fugue, most popular during the Baroque period, as an exercise in logical programming. A fugue played traditionally on a piano even sounds uncanny and automated. And the actual counterpoint notation of a fugue takes the form of a grid, which feels notable in tying it back to Maus’s music anticipating vaporwave, as one of the aesthetic conventions of the genre is the embrace of retro-futuristic grid vector graphics.

Set to a sequence of brothers Charels and Viddy firing assault rifles and handguns in the snow, “Cop Killer” is the one John Maus song used in TFW No GF and also the song featured on MDE: World Peace, the [adult swim] show that was taken off the air for its connections with the alt-right. What is it about Maus’s music and this online milieu? Draw whatever conclusion you want with that.

Forums as oubliettes

In Jim Henson’s Labyrinth, the protagonist Sarah falls into an oubliette on her journey to save her baby half-brother held captive at the center of the labyrinth. Hoggle, the wishy-washy goblin she meets along the way explains, “It’s a place you put people…to forget about ‘em!”

Establishing John Maus’s music as a sort of medieval sensibility repackaged in the ironic dressings of the present allows me to propose the comparison of forums as oubliettes. You can make the argument that the whole internet is an oubliette, but the internet forum as a space is extra akin to falling into a dungeon where the only exit hatch is in its ceiling. The act of clicking on an app is sort of like a descent, dropping down into a specific environment. The main difference is that you voluntarily put yourself there, and a lot of the times you get stuck there. And if we go along with the representations and preconceptions of the subjects featured in TFW No GF, and those who perpetuated the corrupted image of Pepe in Feels Good Man, as societal outcasts, dejected internet-addicted NEETs, irony-poisoned shitposters, and reactionary agitators, then are these forums not just places for them to go to sulk, wallow in anger or self-pity, and lean into the self-fulfilling prophecy of being forgotten about? It feels too harsh and dogmatic to say that conclusively, but the image persists.

The comparison isn’t new. Consider the MUD (multi-user dungeons), PC games like DOOM and QUAKE, and the Windows maze screensaver.

I think of my own experience on 4chan, which was by proxy and consisted of very limited in-and-out lurking. In my quests for full album rips, I would sometimes come across active mediafire links posted in archived /mu/ threads; this was a place where music requests were fulfilled and several folders of whole albums were shared unprompted like offerings, frequently accompanied by brief or extended lines of context to hook new listeners and spread knowledge. It was a place of exchange, digital cultural commodities trafficked from hard drive to hard drive, and where the aspirational quality music has the ability to possess felt more apparent than ever. It could be that it was just the shit I was on the hunt for, but I noticed recurring artists in the old threads I dropped into: Les Rallizes Dénudés, Boards of Canada, Aphex Twin, Grouper, John Maus, (yes, Ariel Pink, too). After a while, they begin to turn into a gestalt of tokens and signifiers. Listen to this album to become this type of person. Download these starter packs if you want to feel any sense of leverage in your communion with the anonymous users in here that you want to feel connected with.

Maybe the internet is more of a requiem, a moratorium, a place where traces of ourselves breed and die, and awareness of that death-imbued quality is what attracts people to music saturated in spectral properties. Maybe it’s because the degradation and distortion of sound mirrors the compressed and manipulated aesthetics of memes. Maybe because it expresses our own corporeal demise.

I don’t think I’ve really answered my initial question, just fell into a labyrinth of my own musings and pattern recognition.

Aaron Anecdotes (Aanecdotes?)

“How much time you spent at the mall?”

—Kanye West, “All Day”

“Motherfucker, you can live at the mall”

—Kendrick Lamar, “Alright”

Malls as loci of social gathering and fulfilling desire and aspiration are approaching the way of the oubliette. In the wake of economic collapse and the general changing retail landscape of the post-postmodern world, we’re hyperaware of instability and the accelerated rate at which market trends fluctuate. The pandemic exacerbated the paradigm shift into fully automated online delivery from the likes of Amazon and other e-commerce services.

Malls are deteriorating at a strange pace. They’re cultural institutions of consumption stuck in stasis. Arguably, they’ve always possessed this quality due in part to the heightened artificiality from which they’re borne. It’s this quality that has made them one of the core spatial symbols of vaporwave. Even when there are tons of people milling about, there’s a sense of imminent collapse whenever you visit one; often you’ll see a boarded up or shuttered business, the remnants of their last advertorial banners still up, plugging a product that might not even be on the market anymore. Palimpsests of the past and the futures the products promised.

Aaron and I were at the Plaza Bonita Mall, located in National City here in San Diego, which still manages to be a booming hub host to a new generation of youth, pandemic notwithstanding.

As we were exiting the mall, we passed by a target practice gallery. I was reminded of the indoor axe throwing venue I saw at a mall the last time I visited Chicago; Aaron recalled a scene from True Stories.

“Shopping malls have replaced the town square as the center of many American cities. Shopping itself has become the activity that brings people together. In here, music’s always playing. What time is it? No time to look back.”

It sounds silly at first, but boutique fair games at the mall make sense when you consider in architectural terms that ‘arcade’ goes as far back to the Hellenistic Period of Ancient Greece and denotes a succession of arched columns. These arched columns were decorative, used to shade walkways, or to house market stalls and shops. The comparison to a town square is proper as it seems to follow a natural trajectory into modernity.

Furthermore, if we look then at architecture as a response to harsh climates and climates defined in more abstract terms, then the consumerism and commodity fetishism taking place in malls is a virtual form of shelter in a similar way that the internal rules, structure, and terms and conditions (or lack thereof) give online forums the durability to harbor communities and protect them from outside “weather.” Both spaces are artificial, atemporal by design, and focal zones of public/private life. The shopping mall has replaced the town square as the center of many American cities and online spaces are gradually rendering the mall and its arcades obsolete.

Though, real estate efforts seem to be attempting to anticipate that obsolescence by incorporating housing in and near mall structures. The Irvine Spectrum is like this, and continual development near the Otay Ranch Mall by my parents’ house indicates Eastlake as a prospective edge city. I bet if I could find my copy of The Poetics of Space, there’d be a Gaston Bachelard quote about mollusks ensconced within shells hidden under barnacles and anemones, or something comparable to living at the mall.

Here are some photos from another recent trip Aaron and I took to Plaza B. We noticed the lights were out at Target. It was a hot day, we had nothing better to do, and we were nosy so we walked in.

Call it pseudo-urban exploration. The internal mechanisms of the big-box store laid bare for all to be reminded of its non-placeness, its artificiality, its ephemerality.

Watching families amble slowly toward the portal of daylight shining through the exit and entrance doors gave us a little glimpse of the impending disintegration track we’re on.

And why should we

Want to go back where we were, how many years?

a looming aughts hipster revival on the horizon?

Is it just me and the spheres I orbit online or has there been an uptick in collective chattering and, by some degree, nostalgia for the mid-00s? There was that (fake?) slideshow paean to American Apparel’s advertising made by a zoomer; this thread on the Cobrasnake.

It’s likely it won’t catch on, but my theory is that it’s coming from a place of anticipatory nostalgia mining from the people who actually lived through that era and also from younger people trying to accelerate to the next recycled trend circuit. Until then, equip yourself with this essential handbook while you wait with bated breath and lament that you donated your gold lamé AA leggings.

Further reading: man who can hear wifi; somehow much of this grinding, anamorphic, so-called “post-internet” music already feels dated; more context on “the most mysterious song on the internet,” which I am still skeptical about; shy boys irl, a short documentary on love-shyness and involuntary celibacy that predates and serves as a contrast to TFW No GF; anemoia, nostalgia for a time you never knew; a scene from “Magnetic Rose” from Katsuhiro Otomo’s Memories; credit to my friend Pablo Dodero for coining the term NuMasc to denote a modern variation of male youth that enlists masculinity while performing vulnerability in the internet age.